On March 28, Cape Cod Times’ Susan Vaughn included Massachusetts Breast Cancer Coalition and Silent Spring Institute in an article titled “Nationwide study to packaging bans: What the Cape can do about PFAS, the forever chemicals.”

“HYANNIS — A program with panelists and two films Saturday afternoon provided much information on the toxic chemical substances called PFAS that are found almost everywhere in our homes, the environment and our bodies.

But the attentive audience of about 75 Cape Cod residents still had plenty of questions for the presenters.

“These forever chemicals are everywhere, in all aspects of life,” Barnstable Town Manager Mark Ells, one of the panelists, said. “The source of it is us, not the water.”

The chemicals, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are the result of the products people use, he added.

The focus in Hyannis has been the drinking water, which once had one of the highest rates of PFAS in the state but has been filtered since 2016. However, Ells stressed the need for education about PFAS, and he was encouraged that young people have become involved in the issue.

“Kids are going to be the ones dealing with the long-term effects,” Luc-Andre Sader of the Barnstable Youth Commission said.

The program was organized by the Youth Commission, Barnstable High School Green Club and Sturgis East Environmental Club, who served as moderators during lengthy question-and-answer sessions after the films on the effects of PFAS on humans and the environment were shown.

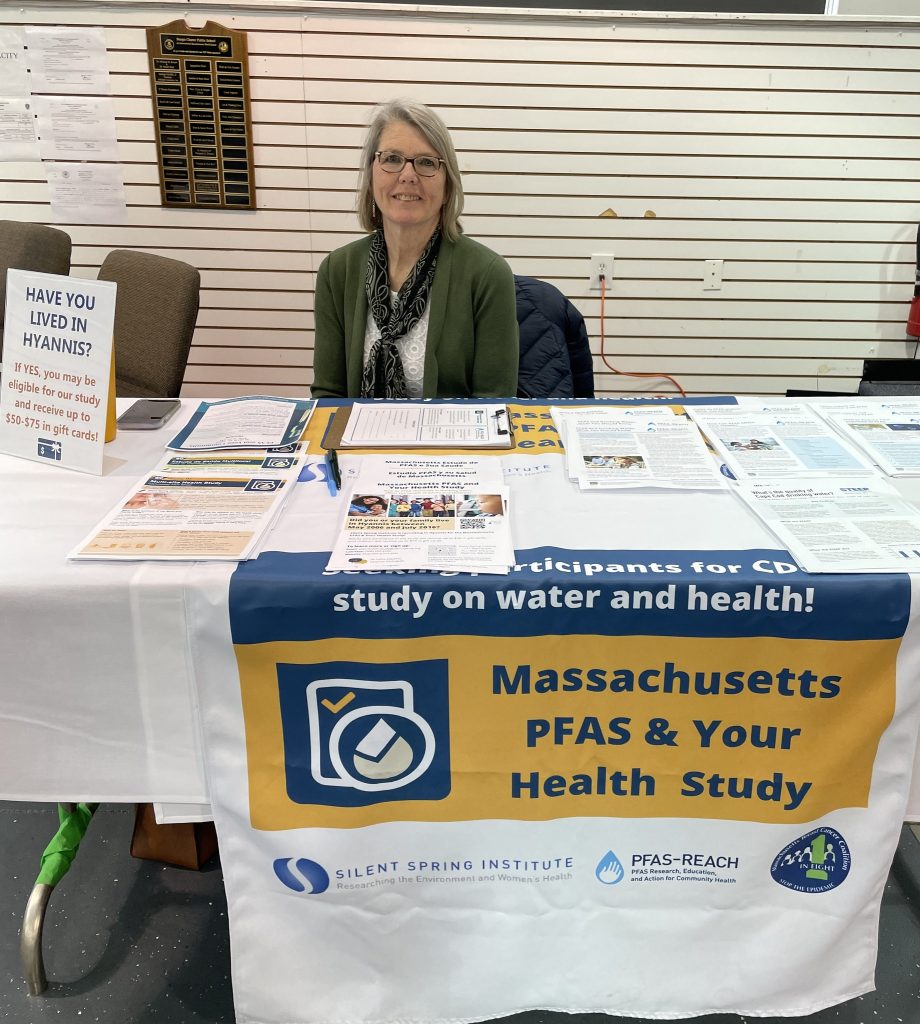

The student groups paired up with Silent Spring Institute, which has been doing environmental studies on the Cape since the 1990s and was the first to identify the PFAS, its lead investigator Laurel Schaider said. The Massachusetts Breast Cancer Coalition was also part of the program as breast cancer is one of several diseases believed to be caused by PFAS.

Silent Spring, based in Centerville, is recruiting Hyannis children, 5-17, and adults who lived in Hyannis from 2006 to 2016 to participate in a nationwide study by the Centers for Disease Control on the effects of PFAS on health. About 300 have participated so far. The goal is 900.

Although few Hyannis residents attended the program, people from other Cape towns came to learn more about PFAS. Some are involved in various environmental projects in their towns.

Theresa Covell of Barnstable, a public health nurse for Barnstable County who is also involved with the Barnstable Clean Water Coalition, brought her two children. She was surprised to learn at the event that PFAS are in most dental floss and is concerned about the Cape’s only aquifer.

A study suggested certain types of consumer behaviors, including flossing, contribute to elevated levels in the body of toxic PFAS chemicals, according to a 2019 website post by Silent Spring Institute.”

Cape residents worry about chemicals from Joint Base Cape Cod.

Phyllis Welby of Osterville is a volunteer for Barnstable Clean Water Coalition, sampling the water in estuaries. She and her husband deliberately chose to build a home away from East Falmouth and Mashpee because of chemicals emanating from training at Joint Base Cape Cod.

A couple from Mashpee said PFAS have been found in the drinking water there and they are also concerned about the foam from the base and all aspects of the environment.

Other questions from the audience were about filters on faucets, treatment of sludge from wastewater plants, effects on shellfish, and whether it can be removed from the body.

It can’t, Schaider said.

Proposed state legislation would ban packaging that uses PFAS by 2030.

State Sen. Julian Cyr, D-Truro, who represents the Cape and Islands, described proposed state legislation from a PFAS task force he co-chaired. It made eight recommendations, including monitoring water and banning all packaging that contains PFAS by 2030. PFAS are found in grease-resistant paper, fast food containers and wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes and candy wrappers as well as Teflon coated pans.

Cyr is particularly concerned about the PFAS in firefighters’ gear.

Greg Milne, a former Barnstable town councilor, asked why the products could not be banned sooner. Cyr said any regulations need a big investment to hire staff to implement them. He said much of the money to pay for the remediations could come from many lawsuits against national companies that have been making the products, some for seven decades.

Before filtering, Hyannis had the highest levels of PFAS in drinking water in 2009.

Milne also asked the presenters to report the highest level of PFAS found in the Hyannis water supply. He said providing the number would encourage more people to participate in the study.

For groundwater — that is, not treated drinking water — Milne said the amount was 320,000 parts per trillion found at the fire training site in 2009.

For drinking water, though, Schaider said that Hyannis had the highest levels of PFAS in the state in 2009 at 430 parts per trillion in tests at the Mary Dunn well near the training site. Massachusetts’ standard now is a maximum PFAS level in drinking water of 20 parts per trillion. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is considering regulations for the first time that would set the standard at 4 parts per trillion, she said.

The PFAS study takes blood and urine samples from participants who receive up to $50 in gift cards for adults and up to $75 for children. To learn more or sign up, Hyannis residents can email pfas-health-study@silentspring.org, call or text 508-296-4298 or check the website https://silentspring.org/project/cdcatsdr-multi-site-health-study-pfas/massachusetts-pfas-and-your-health-study. Individuals can get the test at the Centerville office.